Inhuman People

I have a few personal rules I’ve developed over the years, they’re about how one should act while trying to be a good person and productive at the same time. Two of them are “don’t celebrate anyone’s death” and “seek to help everyone you can, but stop if they don’t want help”. And today I’ll break one of them, “don’t argue with strangers on the internet”. But first, I’ll explain what I thought and how it got tangled in the internet’s madness.

A reasonable life goal is to be successful, whatever it means to you, be it making a lot of money or living peacefully in a remote village with your family. But the ultimate goal is to be remembered as someone good, this means your actions will outlive you. Maybe if you were once good to your neighbor she’ll tell her children a story about you that helps them build their moral compass and will affect them their whole life. The positive externality of being good to others is massive. Most already think similarly, maybe using different words, but what we call fulfillment or happiness boils down to this.

Helping others and being remembered are our terminal goals as humans, making money, getting married, and traveling the world are just instrumental goals. Maybe it doesn’t seem this way at first but the deeper you go the clearer it gets. I like to think about the question “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound” but twist it to a more fitting scenario “If you die and no one remembers you, did you even exist?” The problem is that we’re getting easier to forget and less interested in helping.

Our communities and third places are getting smaller, we don’t see our friends and families as much as we used to. How did this happen? We got alienated by technology, as Paul Graham wrote in 2010, things are getting evermore addictive. Consuming became the norm, and as we stopped creating, and consequently elaborating, we lost the skills to talk to each other. Sure, the barrier to communication fell to the ground but our subjects changed from ourselves to the content we’re currently obsessed with. And if your close group doesn’t want to hear about it or agree with you on something that’s fine, on the web there’ll always be someone who does.

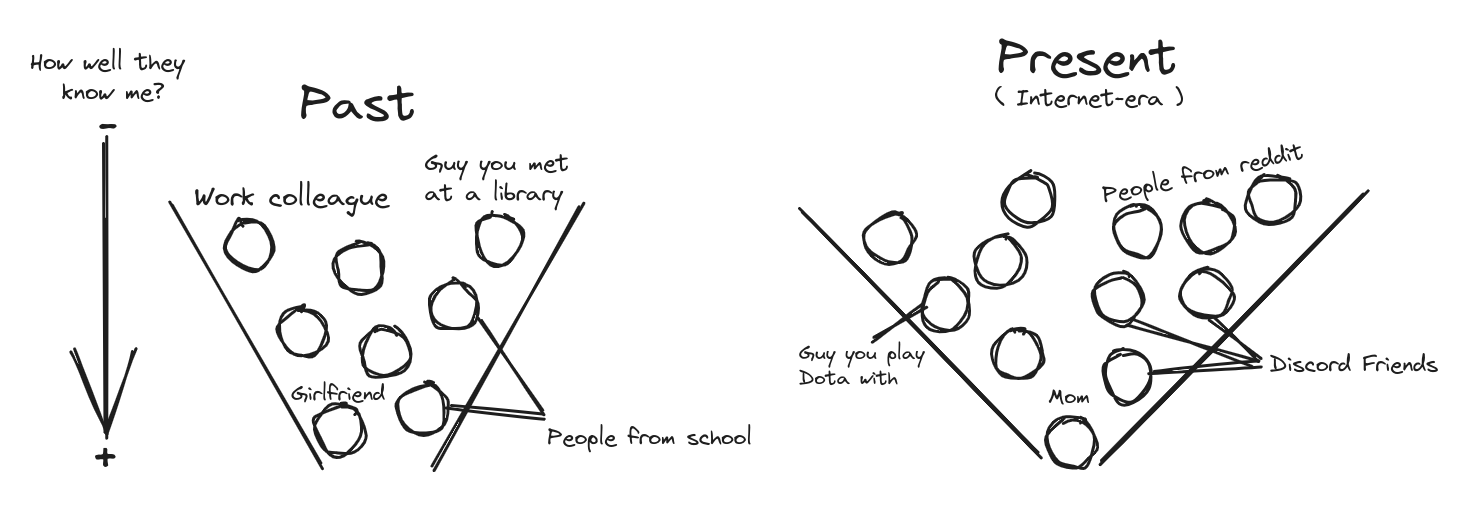

Arguing in favor of decentralized communities is fair, and it indeed made us easier to know about. The thing is that our brains didn’t evolve for the one-to-many communication model of social media. It’s more important to have few strong bonds than a lot of looser ones, being close means more chances of helping and helping on harder problems.

Surely, as we post photos and essays much more people will get to know us, maybe even get in touch and make a call every once in a while. But, can we say more people deeply know us? The top of the funnel got wider, but the end actually shrunk.

The fragility of our relations, made it so that fewer people would correct us on something we said, as in if they did it was easy to find someone who agrees with us. We could stop being wrong, not by iterating on the rationale but by simply not hearing who told us so, sit back and let the algorithm surround you with people who say you are right. But of course, the almighty platform won’t always be able (or want) to bulletproof you from people who think differently, and surely it won’t be of any use with in-person flesh and blood people you’re going to encounter.

This mixture of losing the ability to communicate and forgetting what it feels like to discuss a subject makes whenever we face someone who thinks differently we associate them with an enemy. The other side, the ignorants, people who don’t know what they’re saying. Hence is born the endless internet debate.

Heretic’s Fire

One day, I got a YouTube recommendation for a Lex Fridman Podcast episode, the thumbnail was a pretty white girl and I quote the title Aella: Sex Work, OnlyFans, Porn. At first, I thought, “Hm, that’s different” and didn’t give it much credit, it didn’t seem like something I’d like watching. But, by the tenth time it appeared in my sight, I lost to my curiosity and clicked on it. I must say, it took me about three minutes to realize that my prejudice wasn’t based, it was something I’d liked watching.

Throughout the rest of the episode, I got much more interested and grateful for getting to know someone like Aella existed. There are people who make you rethink the bounds of what’s possible with one’s life and remember how diverse people can be, to me learning about Aaron Swartz was like that, and Aella the same thing. If this is your first time hearing about her, it’s your lucky day! I recommend you read through her substack posts and if you got the time, listen to the podcast.

So, during the week that I was writing this essay you’re currently reading, she posted in her newsletter a piece about how she learned to deal with the hate that is aimed at her. Reading through some of the screenshots she provides is like watching a dog with rabies getting mad at people walking by on the other side of the fence. To the authors of the comments, she wasn’t simply someone they disagreed with or thought was a bad person, her lifestyle and past made it so that nothing she said was valuable. To some her existence was invalid, she wasn’t worth remembering. Their anger came from the public not agreeing with them, they gave her an audience to speak to, and it only made the haters more aggressive. I thought about quoting here a message she shared but figured it’s better not to.

When did we start to be OK with this? Threatening people for living in a way you don’t like? Disgust, that leads to dehumanization, is the feeling that leads to genocide.

Sonder refers to knowing that every person has their own story and life is just as complex as yours, for them, they are the protagonist. In fact, for everyone else, we are just side characters in their lives. Recognizing this is a skill that you get by being curious and learning about other people, it’s your reward for listening. And this realization is something we’re losing as a collective. Haters are people who can’t see past their dogmas, seeing someone find success through different way enrages them.

Aella’s solution was to embrace it as part of her fate. That’s a symptomatic treatment. How can make people remember that on the other side of the screen, there’s someone just like them? I’ve got a joke among friends that a psychological test should be needed for granting people access to the internet, it’s too much power for unauthorized access. Maybe that would fix it. Wouldn’t it be nice if people just were nicer to each other?

Thanks to Gustavo Fior for reading drafts of this.